The Why is Love: Advent and Incarnation

“All this took place to fulfill what the Lord had said through the prophet: ‘The virgin will conceive and give birth to a son, and they will call him Immanuel” (which means “God with us”).’” (Matt. 1: 22-23)

“And the Word became flesh and dwelt among us, and we have seen his glory, the glory as of a father’s only son, full of grace and truth.” (John 1:14)

“For God was pleased to have all his fullness dwell in him, and through him to reconcile to himself all things…” (Col. 1:19-20a)

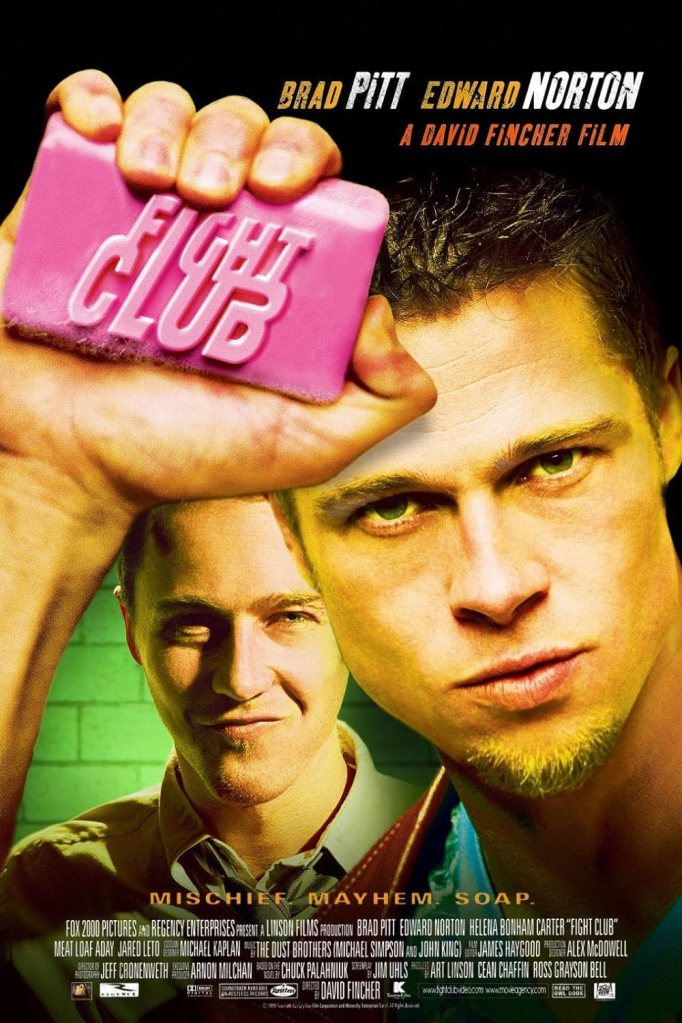

There is a movie by the Coen brothers called Hail, Caesar. The movie is, well, about a movie. A movie studio is filming a movie about the life of Christ through the eyes of a Roman soldier, played by George Clooney, who we find out gets kidnapped. I won’t ruin any more of the plot. If you have ever watched a Coen Brothers movie, you will know that it has witty, dark, dry humour.

And, in my humble opinion, one of the best scenes of the film is also, believe it or not, deeply theological. I think all the best scenes of every film are theological, but whatever.

In this film about a film, Josh Brolin plays the manager of the movie studio, who is shooting this film on the Christ. Brolin, whose character is named Eddie Mannix, knowing this film is going to be the biggest film of the year (think something like the old Ten Commandments or Ben Hur kind of movie), gives a copy of the script to a panel of religious experts: an Eastern Orthodox patriarch, a roman catholic priest, a protestant minister, and a rabbi.

And I know what you are thinking, what next, they all walk into a bar? Not quite.

Brolin’s character explains that this prestige picture is aiming to tell the story of the Christ powerfully and tastefully, so he wants to see if the story is up to snuff.

The Rabbi pipes up: “You do realize that for we Jews any depiction of the Godhead is strictly prohibited.”

Eddie looks at him, disappointed. He had not considered this.

But the Rabbi continues: “Of course, for we Jews, Jesus of Nazareth was not God.”

Eddie looks again, confused but also pleased. He reiterates again that he wants to make sure that the script is realistic and accurate and would not offend any American person’s religion.

The Patriarch blurts out, “I did not like the chariot race scene. I did not think it was realistic.”

Eddie again is confused.

The Priest jumps in: “It isn’t so simple to say that God is Christ or Christ God.”

The Rabbi agrees: “You can say that again, the Nazarene was not God.”

The Patriarch, waxing mystical for a moment, replies: “He is not not God.”

The Rabbi exclaims: “He was a man!”

“Part God also,” says the Protestant Minister.

“No, sir,” says the Rabbi.

To which Eddie turns, trying to smooth things over, but also clearly out of his element: “But Rabbi, don’t we all have a little God in all of us?”

The Priest jumps in again and finishes his thought: “It is not merely that Jesus is God, but he is the Son of God….”

Eddie is now confused: “So are you saying God is all split up?”

“Yes,” says the Priest, “and no,” suggesting it is a paradox.

Eddie is now deeply confused. “I don’t follow…”

The Rabbi interjects: “Young man, you don’t follow for a very simple reason: these men are screwballs! God has children? What, next a dog? A collie, maybe? God doesn’t have children. He’s a bachelor. And very angry!”

The Priest is upset: “He only used to be angry!”

Rabbi: “What, he got over it?”

The minister accuses the Rabbi: “You worship the god of another age!”

The Priest agrees: “Who has no love!”

“Not true!” says the Rabbi, “He likes Jews!”

The minister continues: “No, God loves everyone!”

“God is love,” insists the Priest.

The Patriarch jumps in: “God is who he is.”

Rabbi replies, upset: “This is special? Who isn’t who is?”

Everyone is getting frustrated with each other.

The Priest tries to bring the conversation back around: “But how should God be rendered in a motion picture?”

Rabbi exclaims, exasperated: “This is my whole point: God is not even in the motion picture!”

Eddie turns, sinking into his chair: “Gentlemen, maybe we’re biting off more than we can chew.”

Now, I probably did not do this scene justice. You will have to watch it yourselves. I showed it to my wife, who, for some reason, did not laugh as hard at it as I did.

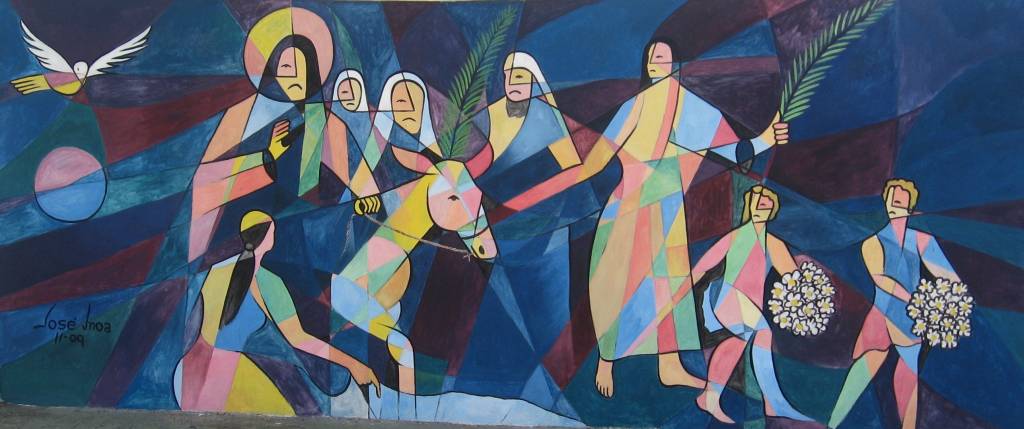

Today, we light the love candle. It is the candle we light on the way to Christmas, where we celebrate the deepest mystery of our faith: the incarnation of Jesus. This Advent season, I have been reading a wonderful little Advent devotional compiled from the writings of Dietrich Bonhoeffer, called God in the Manger (I deeply recommend this to you for next year’s reading). Bonhoeffer was the German pastor who opposed Hitler, sought to organize the church against the power of the Nazis, and was executed, falsely accused of being a part of an assassination plot.

For this week of Advent, the candle of love, the devotional turns to the question of incarnation, why and how is God with us in an infant, born in a stable? Why and how did God become flesh? Why and how was the fullness of deity pleased to dwell here, bodily? How is that possible?

The questions might evoke the same response as Eddie in Hail Caesar: “People, I think we have bitten off more than we can chew!”

Such ideas feel at best unanswerable: above our pay grade as humans. Or at worst illogical, prone to the endless arguing that the Rabbi, Priest, Minister, and Patriarch fell to.

How the Incarnation?

Yet, this question—how and why did God become human?—is the question that all of Christian faith rests on.

How and why did God become human? This week, we light the love candle, and I am going to suggest that incarnation and love—the two are inseparable.

Now, you might insist, that does not really answer the “how” question exactly.

Indeed, let me put the question this way: God is infinite, all-powerful, present to all things, everywhere, all knowing, transcendent, above and beyond all things—how can God be found in human form, let alone the form of a baby?

Put that way, it sounds like trying to fit the ocean into a shot glass. It does not seem like it can work.

Frederick Buechner once said: It feels like a vast joke that the creator of the universe could be found in diapers! He goes on to say, however, that for those of us raised in the church who have grown up with this idea, until we are scandalized by it, we can never take it seriously.

How can God come in human flesh?

As you can imagine, Christian thinkers have found this a bit difficult to answer. Some have said, well, maybe Jesus wasn’t fully human, he only appeared to be human—sort of like how Clark Kent is Superman and only appears to be a mild-mannered reporter. He appears human, but he is actually Kryptonian.

Others came around and suggested that maybe Jesus is not fully God. Perhaps he is like God or has a part of God’s presence in him, but God, the real God, is up in heaven, untarnished by the world, away and transcendent.

Others came around and said, maybe Jesus has the mind of God and the body of a man, or maybe Jesus had something more like a split personality: a divine person in him and a human person in him.

Again, you might be getting the feeling that we have bitten off more than we can chew.

Each of those answers, Christian tradition has found to have its problems. And the ongoing commitment Christians keep coming back to is that in all the ways God is God, Jesus is God. In all the ways humans are humans, Jesus is human, except without sin. Jesus has “two natures.” Well, that still does not answer the question. that still feels like the ocean in the shot glass problem.

Does that mean baby Jesus was omnipotent? Was a little infant, who cannot speak was also all-knowing, knowing about the paths of comets on the other side of the universe? That still sounds like one nature is swallowing up the other.

Bonhoeffer reflects on this problem, and he answers it this way: “Who is this God? This God became human as we became human. He is completely human. Therefore, nothing human is foreign to him. This human being that I am, Jesus was also. About this human being, Jesus Christ, we also say: this one is God. [But] this does not mean that we already know beforehand who God is.”

In other words, Bonhoeffer is trying to tell us that when we look at Jesus, he does not merely fulfill what we expect God to be like in the human Jesus, but he fundamentally redefines God, upsetting our assumption about what God must be like.

He writes, “Mighty God is the name of this Child [based on Isaiah 9:6]. The child in the manger is none other than God himself. Nothing greater can be said: God became a child. In the child of Mary lives the almighty God. [But] Wait a minute!… Here he is, poor like us, miserable and helpless like us, a person of flesh and blood like us, our brother. And yet, he is God…Where is the divinity, where is the might of this child?” Bonhoeffer answers, “In the divine love in which he became like us. His poverty in the manger is his might. In the might of love, he overcomes the chasm between God and humankind…”

How does God, the infinite, transcendent, all-powerful God, become a finite, vulnerable, human baby? The only answer we have is that God is love. Because God is love, God can be all that God needs and wants to be for us. God desires to be with us. So God can.

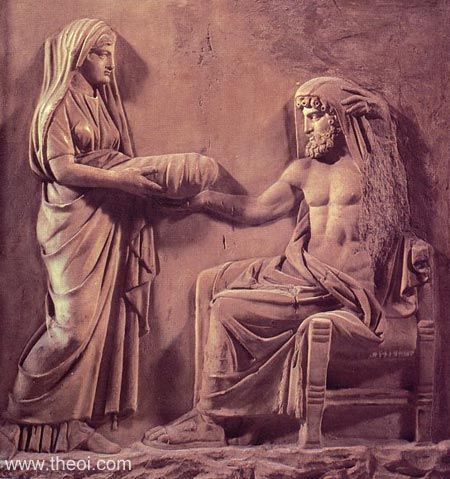

One church father, Gregory of Nyssa, put it this way: God’s true power is to be even things that God is not. For God to become a lowly and vulnerable human, this is not something that contradicts his power, but rather it is proof of his true power, the power of God’s love.

If we start thinking, you know what makes God a God? Power! If what we worship as God is something we understand as power first and foremost, we will forever see the life of Christ as a scandal. Worst still, we will also probably come dangerously close to worshiping human power as something “god-like” as well.

But if God is essentially love, perfect love is capable of drawing close to us in weakness and vulnerability, and that, ironically, is true power.

That still leave my answer somewhat inadequate. I don’t understand all the mysteries of God. But love is the best clue we have.

Thankfully we don’t need to solve theological mysteries in order to trust them and to be saved by them.

Why the incarnation?

Now, if God was able to become human because of love, maybe we need to back the truck up for a second and ask, why? Why did God need to do this?

Afterall, God is portrayed as loving and gracious in the Old Testament. What does Jesus add to it, if we can call it that? Could God just keep telling us that he is love and that God loves us?

Let’s ask it this way: Why does love need a body?

Modern times cast humans as brains on sticks—the fact that many of us live and work barely moving our bodies as we type on computers can lead us to believe this.

We are told messages that we can surpass the limits of our bodies by sheer willpower; some of us, when we were younger, actually believed that. Then you get a sports injury, and next thing you know, your body aches for no reason, and you catch yourself groaning every time you bend over to tie your shoes. Our bodily’s limits catch up with us.

Some of us don’t particularly like our bodies. Our bodies represent our weaknesses, our vulnerabilities, our imperfections. Companies love preying upon our bodily insecurities to sell us more products. Buy this to fix your hair. Buy this to help lose weight. And so on.

Stanley Hauerwas, Professor at Duke University, wrote one of the great books on Christian medical ethics, called Suffering Presence. In it, he reflects on how medical ethics made him profoundly aware of the significance of our bodies.

He tells this one story of a nurse he interviewed. The nurse worked in a branch of the hospital that dealt with severe infections. Severe inflections have a way of making people hate their bodies. I remember one time in high school, I had a severe tissue infection in my forehead, and I woke up looking like a character from The Goonies. Let’s just say it took a few years for my self-esteem to recover.

Well, for some of these folks with severe infections—gangrenous, swollen infections—the nurse reported that often the people would just want their limbs amputated. Faced with the threat of severe infection, some patients quickly concluded their limbs, their bodies, are irredeemable.

What did she do to prevent that mentality? The nurse spoke about how, when she did her rounds, she would make a point of touching the person’s limbs, even if that strictly was not necessary. You can tell a person their limb is okay, but having a person touch their bodies, the nurses said, reminded them that they were worth saving.

Why did God take on human flesh? Why was the fullness of deity pleased to dwell bodily?

To remind us that our bodies are worth saving.

We can start to see why then that the church fought so much about all this theology about Jesus being fully God and fully human: if there was an element of our humanity that God was not apart of fully, not at one with fully, not able to be found there fully, then that part remained unredeemed. If Jesus is not anything less than fully God and fully human, God is not with us.

Because the Incarnation…

There is a hymn that goes like this:

Good is the flesh that the Word has become,

Good is the birthing, the milk in the breast,

Good is the feeding, caressing, and rest,

Good is the body for knowing the world,

Good is the flesh that the Word has become.Good is the body, from cradle to grave,

Growing and ageing, arousing, impaired,

Happy in clothing, or lovingly bared,

Good is the pleasure of God in our flesh.

Good is the flesh that the Word has become.Good is the pleasure of God in our flesh,

Longing in all, as in Jesus, to dwell,

Glad of embracing, and tasting, and smell,

Good is the body, for good and for God,

Good is the flesh that the Word has become.

If you look at so many of the religions around the time of the church, you will see a startling fact: nearly all of them did not care about bodies.

Romans and Greeks often had a deeply tragic outlook on life.

Egyptians were obsessed with escaping this life into an afterlife.

Gnostics believed that if you were spiritual, it did not matter what you did with your body. In fact, salvation was found in escaping from your body. The body was evil.

Eating and bathing, sex and sleep, for many, these were fallen and evil things. Sadly, there are a lot of Christians who still have that mentality today: to be spiritual is in some way to disregard your body, get away from it. The body, for some, is at best an obstacle to be conquered and, worse, a thing to be ashamed of.

However, one reason why Christianity grew in the ancient world is that it rested on a revolutionary truth for people: If God became human, you matter. The incarnation says that God made the world very good. The goodness of creation is a part of what it means to have a body, the body God gives us, the body God is pleased to dwell in. Your life matters.

Because God took on flesh, because God was found in a body, there is nothing we experience that is meaningless to God.

Our hunger and needs, our frustrations and pleasures, our vulnerabilities and our strengths, our desires and dreams, our thoughts and emotions, every event, right down to every mundane moment, these all matter to God. God is found there.

What writer says the message of the incarnation means that “there is nothing so secular that it cannot be sacred” (Madeleine L’Engle).

Whether it is singing in church, answering emails at work, eating a bowl of cereal in the morning, or lying still at night: every moment can be the site where God meets with us. Every moment can be a place where we know God’s love finds us. Why? God came in Jesus, God Immanuel: God with us.

And because God took on flesh, we also know God will never let us go. No matter who we are or what we have done. God is on our side. Paul puts it this way:

“For I am convinced that neither death nor life, neither angels nor demons, neither the present nor the future, nor any powers, neither height nor depth, nor anything else in all creation, will be able to separate us from the love of God that is in Christ Jesus our Lord.” (Rom. 8:38-39)

How did God become human? Why did God become flesh? How do we know we have forgiveness and hope? This morning, we lit the love candle. In it, we have the foundation of our faith: Because God loves us so much, because God is love, God became one of us.

Let’s pray: